Sake 101 #5: 10 Questions Wine Lovers Ask (and Why They Matter)

I’ve been asked these questions over and over—so I wrote them down, once and for all.

📍Who This Is For

If you work in wine retail, lead tastings, or want to talk about sake with more confidence—this post is for you. Not in the trade? You’ll still enjoy the journey (and maybe find a new favorite bottle).

I’m Kazumi, a DipWSET and wine and sake educator based in Amsterdam. With a background in both Japanese and European food culture, I write this Sake 101 series every Tuesday to bridge the gap—translating sake into the language of wine professionals.

Each week, I explore one topic to help demystify sake, deepen your understanding, and give you clear, practical language to use on the floor or at the table.

This week’s theme: 10 questions and misconceptions I often hear from wine lovers.

Why I Wrote This Post

As someone surrounded by wine professionals, I’m lucky to be part of a culture where curiosity thrives. Many of my friends and colleagues in the wine world—sommeliers, educators, importers—have started asking thoughtful questions of each other. I love that.

There’s something truly special about the wine community’s openness. Even when sake feels unfamiliar, people don’t hesitate to ask questions, share experiences, and invite each other into new conversations. It’s inclusive, professional, and always eager to learn more.

Over time, I’ve noticed a few questions that keep coming up—things that seem obvious from inside the sake world, but are totally fair to wonder about when you’re coming from wine. So this week’s Sake 101 is dedicated to those moments.

These are the top 10 questions or misunderstandings I’ve heard from wine lovers or even pros. They’re based on my own conversations and experiences—not a rulebook.

Have a question you've been wondering about? Leave a comment. I’d love to answer it—or include it in a future edition. Let’s get started. (All the sake examples mentioned are exported from Japan, though availability may vary by market.)

1. Is sake more alcoholic than wine?

Typically, yes. Most sake ranges from 14% to 16% ABV (alcohol by volume), slightly higher than the average still wine, which generally falls between 11% and 14% ABV. Certain undiluted styles, known as genshu, can reach up to 18% to 20% ABV, adding notable weight and intensity to the beverage.

Despite its higher alcohol content, sake often feels smoother and gentler on the palate. This is due to its low acidity and tannin levels, coupled with a rounded, soft texture. Many first-time drinkers are pleasantly surprised by how approachable it is, even at higher alcohol levels.

After brewing, most sake is diluted with water to fine-tune the alcohol content and mouthfeel, resulting in a beverage that is both easy-drinking and food-friendly.

For those seeking beverages with reduced alcohol content, there are low-alcohol sake options available. These may be naturally fermented to a lower ABV or diluted to achieve the desired alcohol content.

Sparkling sake typically has an alcohol content ranging from 4% to 16% ABV, depending on the brewing method and style. For instance, one of my favorites, Shichiken "Yama no Kasumi" Sparkling Sake is an elegant sparkling sake has an alcohol content of 11% ABV. Crafted through secondary bottle fermentation, it offers a light, refreshing experience with a subtle effervescence. These lower alcohol levels, combined with the effervescence, make sparkling sake a popular choice for those seeking a lighter and more refreshing beverage.

2. Is a lower polishing ratio always better in sake?

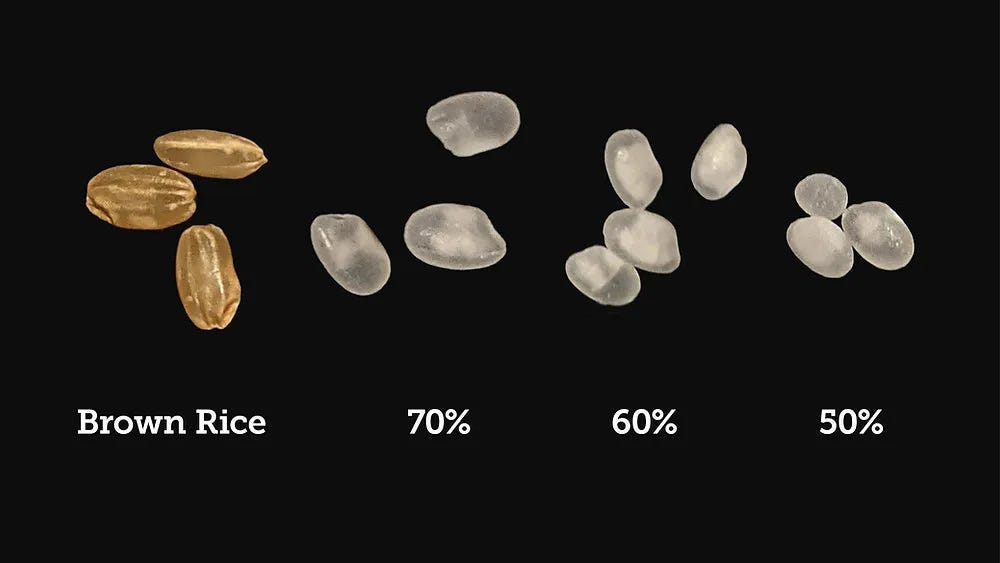

The polishing ratio is a crucial concept in sake brewing, indicating the percentage of the rice grain that remains after milling. For instance, a polishing ratio of 70% means that 30% of the outer layer has been milled away, leaving 70% of the grain intact. Similarly, a 50% polishing ratio signifies that the rice has been polished down to half its original size.

Rice grains consist of multiple layers: the outer bran, the endosperm, and the starchy core. Polishing removes the bran and some of the protein-rich endosperm. While nutrients like proteins and fats are essential in brewing, excessive amounts can lead to coarse or unbalanced flavors. Generally, more polishing results in lighter, more aromatic sake, whereas less-polished styles often offer greater umami, structure, and pairing flexibility.

A common misconception arises from the association between polishing ratios and sake classifications. Grades like Junmai Daiginjo (typically polished to 50% or less) and Ginjo (up to 60%) are often perceived as superior due to their higher price points. However, the polishing ratio is not an absolute indicator of quality. Context—and cuisine—matters. Sake with higher polishing ratios can be exceptional, offering rich flavors that pair well with various dishes. Therefore, while the polishing ratio influences style and flavor, it should not be the sole determinant of a sake's quality or suitability for a particular occasion

👉 Learn more: Sake 101: The Role of Polishing Ratio

3. Does sake improve with age like wine?

In most cases, no. Unlike many wines that benefit from cellaring, most sake is crafted to be enjoyed young. Brewers design it to showcase freshness, balance, and purity within a relatively short window—usually within a year or two of bottling. Sake’s structure is quite different from wine: it’s typically low in acidity, contains no tannins, and is often pasteurized and filtered. These factors all limit its aging potential.

That said, there are fascinating exceptions. Some brewers deliberately age their sake, producing what’s known as koshu (aged sake). These sakes can take on a deep amber hue and develop layered aromas of nuts, caramel, dried fruit, and soy sauce. Much of this complexity comes from slow Maillard reactions—a form of non-enzymatic browning that occurs between sugars and amino acids over time. In aged sake, it creates a mellow, savory depth that’s unlike anything in young, fresh styles.

Still, aged sake remains a niche in Japan. There’s no standardized vintage labeling system and the style varies depending on breweries. While many breweries stay cautious, a few producers are pushing boundaries. Breweries like Daishichi and Kamoizumi offer matured expressions, and Masuizumi has even aged sake in Burgundy and Champagne barrels to explore new textures and aromatics.

So while most sake is meant to be enjoyed within a year or two, aged sake—when done thoughtfully—can reveal a beautiful, oxidative richness. It's not for everyone, but for the adventurous palate, it's a rewarding world to explore.

👉 Learn more: What Connects Champagne, Sauternes & Aged Sake?

4. Is high acidity important in sake as it is in wine pairing?

Not quite. In wine, acidity is a key player in balancing flavors and cutting through fat, salt, or sweetness. But in sake, the structure is different. Sake naturally has much lower acidity than wine, and it contains no tannins. Its pairing power comes more from umami and texture than from sharp, palate-cleansing acidity.

That said, some traditional styles—like Kimoto and Yamahai—develop naturally higher levels of acidity. This happens during the fermentation starter phase, where lactic acid bacteria are encouraged to grow slowly and contribute more complexity. These sakes tend to have a firmer grip on the palate and pair especially well with rich, creamy, or fermented dishes, such as aged cheese or soy-based stews.

Other factors, like yeast strain and koji mold type, can also influence the acidity to some degree. For example, certain yeasts produce more succinic or lactic acid, giving the sake a savory or slightly tangy edge. But overall, acidity plays a supporting role in sake pairing—unlike in wine, where it's often the star of the show.

5. Is sparkling sake just carbonated regular sake?

Not exactly. While some sparkling sake is made by force-carbonating regular sake—just like soda water—many high-quality sparkling sakes go through natural in-bottle fermentation, similar to Champagne. This method creates bubbles through yeast activity, not added gas.

One key difference from wine is that sake mash already contains sugar in the form of glucose, thanks to the action of koji breaking down the rice starch. That means brewers don’t need to add sugar for the second fermentation, as is typical in traditional method.

In naturally sparkling sake, fermentation is usually paused when the alcohol level is still low (around 5–10%), and then resumed in the bottle to create fine bubbles and slightly higher alcohol—usually ending around 6–12% ABV. Some brewers disgorge the bottle like in Champagne, while others leave the lees in for a cloudy, textured finish.

So no—sparkling sake isn’t just regular sake with fizz. It’s often crafted with its own distinct method and character, and it pairs beautifully with fried or spicy foods thanks to its light body, low alcohol, and gentle sweetness.

6. Is there such a thing as terroir in sake?

Yes—but it manifests differently than it does in wine. In wine, terroir is typically expressed through climate, soil, vineyard location, and local grape varieties. In sake, the concept is still evolving, but factors like water source, rice variety, local climate, and regional brewing traditions all contribute to a sense of place.

Water plays an especially important role. Japanese brewing water tends to be very soft—low in minerals like calcium and magnesium—which affects fermentation speed and yeast activity. This softness is one reason many sakes have a smooth, gentle texture. Regions like Kyoto (Fushimi) and Hiroshima are known for their soft, elegant styles thanks to this kind of water.

In contrast, areas like Nada in Hyogo Prefecture use miyamizu—a naturally harder, mineral-rich water—which tends to produce drier, more structured sake. Still, compared to European water, which is often much harder (especially in places like Germany or northern Italy), the difference between water sources within Japan can feel subtle to the untrained palate. You might not immediately notice the shift from Kyoto’s softness to Nada’s firmness—but it's there, shaping the style in quiet, powerful ways.

7. Is sake yeast the same as wine yeast?

No. While both are strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sake yeast is specially selected to thrive in high-alcohol environments—very different from wine must. These strains also produce distinct fruity esters, such as banana (isoamyl acetate) and melon or apple (ethyl caproate), depending on the yeast type. Sake yeast’s ability to work with koji enzymes and maintain fermentation in very cold conditions is also unique—supporting slow, clean flavor development.

Kyokai yeasts are cultured strains developed and distributed by the Brewing Society of Japan (a.k.a. Nihon Jozo Kyokai). According to Brewing Society of Japan, each numbered strain—like #6, #7, #9, or the highly aromatic #1801—offers different aromatic and fermentation characteristics. Brewers often choose yeast as a key stylistic tool, similar to how winemakers might select strains for tropical fruit, floral, or neutral expressions.

In recent years, some innovative brewers have begun experimenting with alternative yeasts—including wine yeast, yogurt/cheese-related yeasts, and wild ambient yeasts from the brewery environment. These approaches often aim to create more expressive, unconventional aromas, or to mimic natural wine practices. While still niche, this trend is helping expand the stylistic range of sake beyond the classic Kyokai strains.

8. Why is sake usually served in small cups?

Traditionally, sake is poured into small cups (ochoko) to encourage social rituals—guests pour for each other rather than themselves, reinforcing hospitality and attentiveness at the table. These cups also help control portion size, which matters when drinking higher-alcohol sake over time.

From a sensory perspective, small ceramic cups don’t emphasize aroma, which suited traditional sake styles that focused more on umami and texture. However, in modern tastings, wine glasses are increasingly used to showcase fruity or floral aromatics—especially in Ginjo and Daiginjo styles.

9. Is sake meant to be drunk warm or cold?

Both, actually—and it depends on the style. Rich, full-bodied sake like Junmai or Kimoto often shines when gently warmed (around 45–55°C), which enhances umami and softens any sharp edges. In contrast, delicate, aromatic styles such as Ginjo or Daiginjo are best served chilled (10–15°C) to preserve their fruity and floral notes.

Temperature is one of the most underused tools in sake service. Unlike wine, where room or cellar temperature dominates, sake spans a wide range—from 5°C to 55°C. A single bottle can express entirely different qualities depending on how it’s served.

Chilled (5–10°C) is ideal for sparkling, Ginjo, Daiginjo, or light-bodied styles. With dishes like sashimi, fresh oysters, green salads with citrus dressing, or light tempura, cool sake amplifies freshness and keeps the palate lively.

Warm to hot (45–55°C) suits richer styles such as Junmai, Kimoto, or Yamahai. These temperatures bring out comforting depth in dishes like Japanese hot pot (nabe), sukiyaki, braised pork belly, or beef stew. Warm sake also complements aged cheeses or earthy mushrooms, highlighting savory and umami elements with mellow balance.

👉 Learn more: From Dom Pérignon to Sake: A Game-Changing Creation

10. Can sake go bad once opened?

Yes, sake can go bad once opened—but not as quickly or dramatically as wine. Most sake stays fresh for about one to two weeks after opening, especially if kept in the fridge and properly sealed. Pasteurized sake (which makes up the majority of sake on the market) is generally more stable. Unpasteurized styles, known as nama-zake, are more sensitive to oxygen, heat, and light, and should be consumed within a few days.

Unlike wine, sake doesn’t typically oxidize into sharp or vinegary flavors. Instead, it gradually loses its aromatic brightness and texture, becoming dull, flat, or slightly off-smelling. However, if stored poorly—especially in warm or bright conditions— then more noticeable faults can develop.

The most common storage-related issues include:

Oxidation: Extended exposure to air causes aromas to fade and the flavor to flatten. Sake can take on a stale, cardboard-like note.

Light damage: Exposure to sunlight or fluorescent light can create unpleasant aromas resembling cooked cabbage or wet wool, especially in unpasteurized or clear-bottle sakes.

Heat spoilage: High temperatures can accelerate chemical breakdown and lead to musty, sour, or soy-sauce-like off-flavors.

For those pouring by the glass or savoring a premium bottle over several days, a wine preserver (like a vacuum pump or argon spray) can help extend freshness. Store opened bottles upright in the fridge and avoid light exposure. And if you're not sure? Trust your nose and palate—fresh sake should smell clean, soft, and inviting.

Let’s Trade Ideas

Which of these questions have you heard before—or asked yourself? If you like this style, I would make the second edition, so let me know if you have any questions!

💬 Leave a comment or share this post with a fellow wine lover or educator. I’d love to hear your story—and maybe feature it in a future edition.

This post is part of my Tuesday Sake 101 series, where I explore the foundations of sake through a wine-savvy lens. It pairs with my Friday pairing series, where I share unexpected food & wine (or sake) combinations from across Asia and beyond.

👉 If you found this useful, subscribe to get each week’s edition in your inbox—and feel more confident recommending sake at your shop, bar, or table.

Thanks for reading Pairing the World: Wine, Sake, and More!

Subscribe for free to support this work and keep the conversation going. 🍶🍷

ワイン好きからよく聞かれる10の質問と、その理由

これまで何度も聞かれてきた質問を、まとめて答えてみました。

📍この記事はこんな人におすすめ

ワインショップで働いている方、テイスティングを担当している方、お客様にもっと自信を持って日本酒の話をしたい方へ。

もちろん業界関係者でなくても、きっと楽しんで読んでもらえるはず。もしかしたら、新しいお気に入りのお酒に出会えるかもしれません。

こんにちは、オランダ・アムステルダムを拠点に活動しているKazumiです。DipWSET(WSET Diploma)を持ち、ワインと日本酒の講師をしています。

火曜日に連載しているこの「Sake 101」シリーズでは、ワインの知識がある方にも日本酒をもっと身近に感じてもらえるよう、毎回ひとつのテーマを取り上げてやさしく解説しています。

今週のテーマは、ワイン好きの方からよく聞かれる10の質問。

私のまわりのソムリエやインポーター、講師仲間たちとの会話から生まれた内容です。

なぜこの記事を書いたか

ワイン業界には、知識への探究心があふれています。だからこそ、日本酒のこともたくさん質問されるようになりました。

その中には、日本酒の世界では当たり前のことでも、ワインの視点から見ると「ちょっと不思議」に思えるものもたくさん。

今回はそんな「なるほど!」という気づきが詰まった質問を10個、私の言葉でまとめました。

もし気になることがあれば、コメントでぜひ教えてくださいね。今後の投稿で取り上げるかもしれません!

では、はじめましょう。

※紹介している日本酒はすべて日本から輸出されているものですが、国や地域によって流通状況は異なることがあります。

1. 日本酒ってワインよりアルコール度数が高いの?

はい、基本的にはそうです。

日本酒のアルコール度数は通常14〜16%で、スティルワイン(白・赤)の11〜14%よりやや高めです。

「原酒(げんしゅ)」と呼ばれる加水していないタイプだと18〜20%になることもあり、飲みごたえがあります。

とはいえ、多くの人が「思ったより飲みやすい」と感じるのが日本酒の不思議なところ。酸やタンニンが少なく、口当たりがやわらかいからです。

通常、日本酒は最後に水を加えて、アルコール度数と口当たりのバランスを整えて出荷されます。そのため、食事に合わせやすく、飲み疲れしにくいのも特徴。

最近では、低アルコールの日本酒も増えていて、自然発酵で度数を抑えたものや、加水によって調整されたタイプもあります。

ちなみにスパークリング日本酒は、製法によって4〜16%までさまざま。

私のお気に入りのひとつ「七賢・山ノ霞」は11%。瓶内二次発酵で造られていて、きめ細やかな泡と爽やかさが魅力です。

2. 精米歩合が低いほど、いい日本酒なの?

そうとは限りません。

精米歩合とは、米の表面をどれくらい削ったかを表す数値。たとえば「精米歩合70%」なら、お米の30%を削り、70%を残した状態ということになります。

一般的には、削るほど(=歩合が低いほど)香りが華やかで軽やかな味わいに仕上がりやすく、「吟醸」や「大吟醸」といった高級酒にも多く使われます。

でも実は、精米歩合が高め(あまり削っていない)でも、旨味がしっかり感じられ、料理に合わせやすい日本酒がたくさんあります。

精米歩合はあくまでスタイルの違いを示す目安であり、品質の良し悪しを決めるものではありません。

👉 詳しくはこちら:Sake 101「精米歩合の役割」

3. 日本酒もワインのように熟成で美味しくなるの?

基本的には、「若いうちに飲む」のが前提で造られています。

酸が少なく、タンニンもない日本酒は、ワインと違って長期熟成にはあまり向きません。一般的には瓶詰めから1〜2年以内が飲み頃です。

ただし、例外もあります。「古酒(こしゅ)」と呼ばれる熟成酒は、時間とともにナッツやカラメル、干し果物のような複雑な香りを帯び、琥珀色に変化していきます。

こうした風味の変化は、アミノ酸と糖がゆっくり反応する“メイラード反応”によるもの。コクと深みのある味わいが特徴です。

まだまだニッチなジャンルですが、「大七」や「賀茂泉」などが古酒を手がけており、「満寿泉」ではブルゴーニュやシャンパーニュの樽で熟成させた挑戦的な商品も登場しています。

👉 詳しくはこちら:熟成酒とシャンパーニュ、ソーテルヌの意外な共通点

4. 食事に合わせるには、やっぱり酸が大事?

日本酒の場合、そうでもありません。

ワインでは酸が味のバランスを整えたり、脂や塩気を切ってくれる重要な役割を果たしますが、日本酒は酸が少なく、その代わりに「旨味」や「質感」で料理と調和します。

ただし、酸がやや高めの伝統的スタイルもあります。たとえば「生酛(きもと)」や「山廃(やまはい)」と呼ばれるタイプは、自然に乳酸菌を増やして複雑な味わいを引き出します。

クリーミーな料理や発酵食品と合わせると抜群に合いますよ。

5. スパークリング日本酒って、ただの炭酸入り?

いいえ、実はそうではありません。

たしかに炭酸ガスを後から注入するタイプもありますが、高品質なスパークリング日本酒の多くは、瓶内二次発酵という伝統的な方法で造られています。これはシャンパーニュと同じ製法です。

日本酒の場合、麹が米のでんぷんをブドウ糖に変えてくれるので、二次発酵のために砂糖を加える必要がありません。

発酵をいったん止めて、まだアルコール度数が5〜10%くらいの段階で瓶詰めし、そこで再び発酵を進めて泡を生み出します。最終的にアルコールは6〜12%くらいに仕上がります。

造り手によっては、澱(おり)を取り除いて透明に仕上げるところもあれば、あえて澱を残してにごりのあるタイプにすることもあります。

つまり、スパークリング日本酒は単なる「炭酸入りのお酒」ではなく、製法も味わいも独自の世界。軽やかな飲み心地とやさしい甘みで、揚げ物やスパイシーな料理とも相性抜群です。

6. 日本酒にもテロワールってあるの?

はい、あります。でもワインとは少し形が違います。

ワインでのテロワールは、土壌や気候、畑の位置などが中心ですよね。日本酒では、水、米、気候、そして地域ごとの醸造スタイルがその土地らしさを生み出します。

特に「水」はとても重要。日本の仕込み水はカルシウムやマグネシウムなどのミネラルが少なく、とてもやわらかいのが特徴です。

たとえば、京都・伏見や広島などはやさしい口当たりの酒で知られています。逆に、兵庫・灘では「宮水(みやみず)」という硬水が使われ、キリッとした辛口の酒が多いです。

ヨーロッパの硬水と比べるとその差は微妙かもしれませんが、日本国内ではこの「水の違い」がスタイルに大きく影響します。

7. 日本酒の酵母って、ワインの酵母と同じ?

基本的には同じ**酵母の種類(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)**ですが、性質が大きく違います。

日本酒用の酵母は、高いアルコール環境でも働けるように選抜されていて、寒い温度でもきれいに発酵が進みます。

さらに酵母によって「バナナ(酢酸イソアミル)」や「メロン・リンゴ(カプロン酸エチル)」など、香りのタイプが変わります。

有名な「協会酵母(きょうかいこうぼ)」は、日本醸造協会が配布している番号付きの酵母。たとえば6号、7号、9号、そして華やかな香りの1801号などがあります。

最近では、ワイン酵母やチーズ・ヨーグルト由来の酵母、蔵に自然にいる野生酵母などを使って、個性的な酒を造る試みも増えてきました。自然派ワインに近い感覚で、日本酒の幅がどんどん広がっています。

8. なんで日本酒は小さいカップで飲むの?

これは日本ならではのおもてなし文化から来ています。

「おちょこ」や「ぐい呑み」と呼ばれる小さな器で飲むことで、お互いに注ぎ合うというコミュニケーションが生まれます。自分では注がず、相手の器に気を配る—そんな気持ちの表れですね。

また、アルコール度数が高めなので、小さい器でちょっとずつ楽しむのにも理にかなっています。

ただし、近年ではワイングラスで日本酒を提供するお店も増えてきました。特に吟醸や大吟醸のように香りが華やかなタイプは、ワイングラスの方が香りを引き立ててくれます。

9. 日本酒は冷やして飲むの?温めるの?

どちらも正解です!スタイルによって合う温度が違います。

コクがあって旨味が強い「純米酒」や「生酛(きもと)」などは、**ぬる燗(45〜55℃)**にすることでまろやかになり、料理との相性もぐっと良くなります。

一方、華やかな香りの「吟醸」「大吟醸」タイプは、**冷やして(10〜15℃)**飲むことでフルーティな香りが引き立ちます。

日本酒はワインよりも幅広い温度帯で楽しめるお酒なんです。冷蔵庫でしっかり冷やして爽やかに、あるいは温めてほっこりと。ひとつのお酒でいろんな表情を楽しめるのも魅力です。

👉 詳しくはこちら:ドン・ペリニヨンから学ぶ、日本酒の温度の可能性

10. 日本酒って開けたらすぐ悪くなる?

ワインほどではありませんが、開封後は鮮度が落ちていきます。

一般的には、冷蔵保存すれば1〜2週間ほど美味しく飲めます。特に加熱処理されたタイプ(火入れ)は安定しており、ゆっくり楽しめます。

ただし、「生酒(なまざけ)」のように加熱処理していないものはデリケートで、開けたら早めに飲み切るのがベター。

劣化すると、酸っぱくなるというよりは、香りや味わいがぼやけてしまったり、段ボールのようなにおいが出てくることがあります。

高温や光にも弱いので、冷蔵庫で立てて保管し、なるべく早めに飲み切るのがおすすめです。ワイン用のバキュームポンプやアルゴンスプレーも、日本酒に使えますよ!

💬 あなたの質問も聞かせてください

この記事で紹介した質問、聞いたことがあるものはありましたか?それともご自身が気になっていたことも?

ご好評いただければ、第2弾も作ります。気になることがあれば、ぜひコメントで教えてくださいね。

この投稿は、毎週火曜日に更新している「Sake 101」シリーズの一部です。金曜日には、アジア料理とワイン/日本酒の意外なペアリングを紹介する連載もやっています。

👉 面白いと思ったら、ぜひ購読してください。毎週の配信で、日本酒をもっと自信を持っておすすめできるようになりますよ!

読んでくださってありがとうございます!

「Pairing the World: Wine, Sake, and More!」は、ワインと日本酒の世界をつなぐブログです。購読は無料です。お気軽にどうぞ🍶🍷

また、日本ワイン、日本酒に関し(オランダから)プロモーションや通訳等のお手伝いをしていきたいと思っています。何かお手伝いできることがありましたらこちらまでご連絡いただければ幸いです。

Thanks for all the useful information