Sake Interview #4: Hakushika—The Serendipitous Discovery

How an Established Nada Brewery Redefined Aged Nihonshu

**🇯🇵 日本語版は記事の下部にあります / Japanese version available below**

This is an interview with Tatsuuma-Honke Brewing Company on crafting prized aged sake. Discover their unexpected journey into the ancient art of aged nihonshu*(Japanese sake).

📍Who This Is For

Curious about sake? Hear directly from the person who makes it. Whether you work in wine retail or hospitality—or simply enjoy discovering standout bottles at home—this post is for you.

I'm Kazumi, a DipWSET and educator based in Amsterdam. With a background in wine and sake, I translate sake through a wine-savvy lens.

*Nihonshu: The GI-protected official term for Japanese sake

Introduction: The Unexpected Discovery

The sugar-coated pecan nuts disappeared from my plate with alarming speed. At ProWein's master class, the Maillard reaction aromas from Hakushika's 10-year koshu created a collaboration with those sweet, crunchy pecans that was dangerously addictive—I could have eaten them forever.

Later, wandering through the trade fair, I found myself at Hakushika's booth, still thinking about that remarkable pairing. When I asked company president Tatsuuma-san about how their koshu came to be, his answer was surprisingly humble: "It was a serendipitous discovery."

That phrase sparked my curiosity, leading me to interview the people behind this exceptional koshu.

Heritage & Foundation: 363 Years of Brewing Excellence

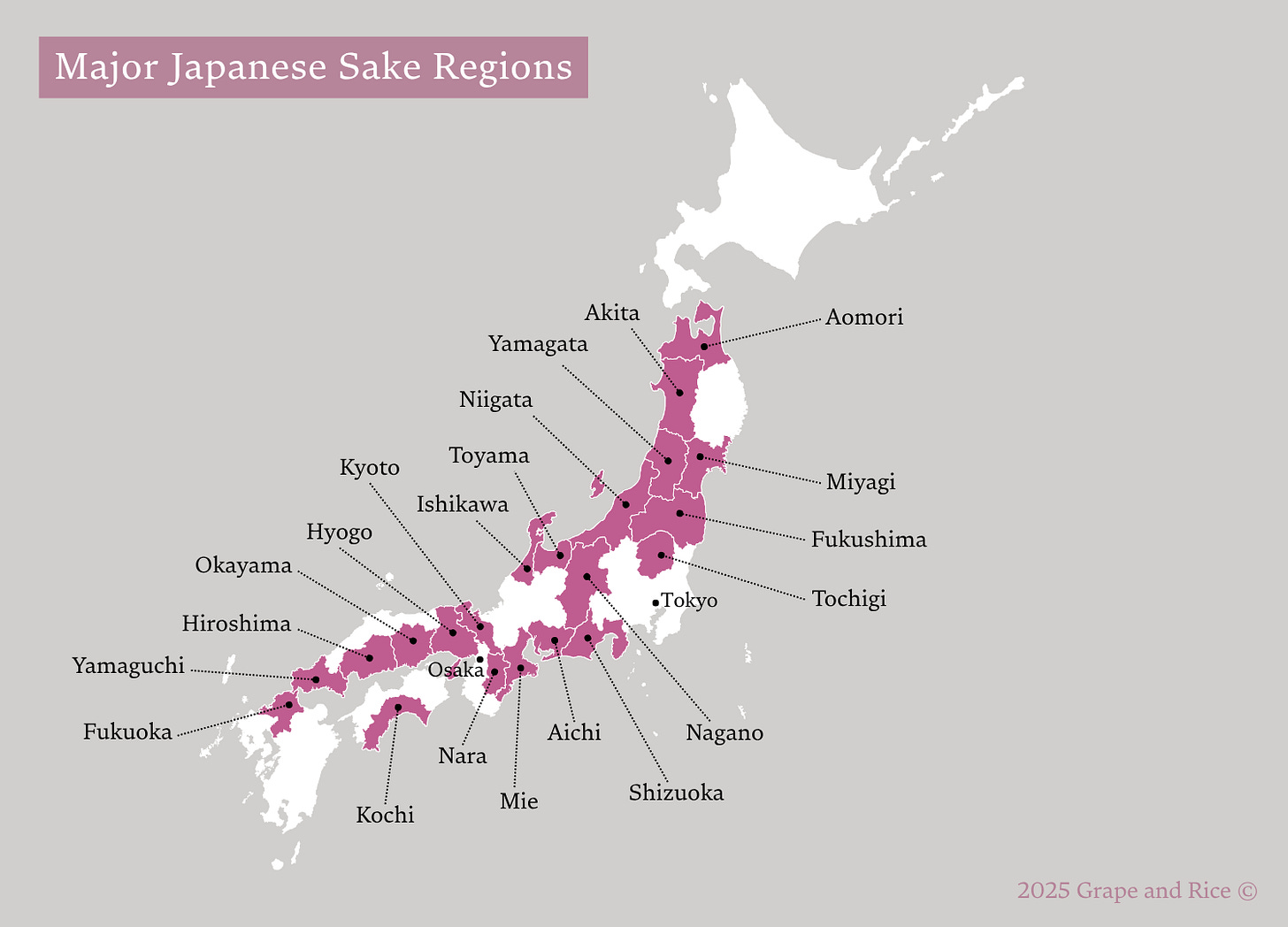

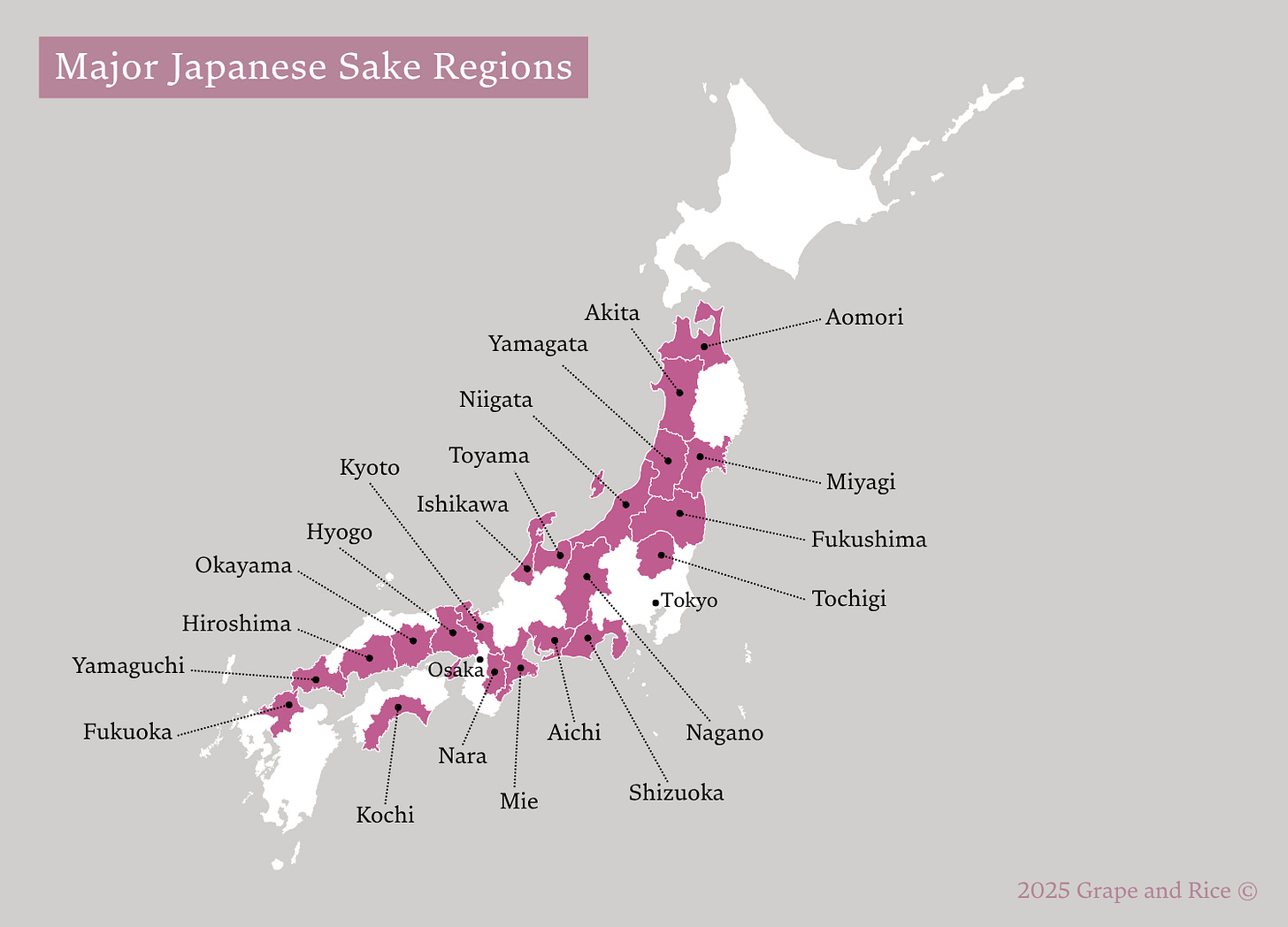

Hyogo Prefecture produces approximately 30% of Japan's domestic nihonshu and ranks as the nation's top nihonshu-producing region. Within Hyogo, the Nada district between Osaka and Kobe is renowned as Japan's finest nihonshu production area, home to numerous prestigious breweries including Hakushika.

Tatsuuma-Honke Brewing Company, an established sake brewery , has been crafting nihonshu since 1662 in Nishinomiya's legendary Nada district. Founded by Kichizaemon Tatsuuma during Japan's Edo period, this family business now operates under its 15th-generation leadership—a remarkable continuity spanning nearly four centuries.

The name "Hakushika" (白鹿) means "white deer," drawn from a Chinese legend of an emperor who encountered a thousand-year-old white deer wearing a bronze medallion in his palace gardens. The deer became a symbol of longevity and good fortune—an apt metaphor for the brewery's enduring legacy.

Located in the heart of Nada, Hakushika benefits from "miyamizu"—the famous brewing water from the Rokko Mountains that has made this region synonymous with premium nihonshu production. The brewery's philosophy centers on creating "umami-rich nihonshu that harmonizes with food." This approach to sake-making would prove particularly well-suited to their later koshu development.

The Lost Tradition: From Samurai Luxury to Tax-Driven Extinction

To understand why Hakushika's discovery felt serendipitous, we must first understand why aged nihonshu became so rare. Until the end of the Edo period (1603-1867), aged nihonshu was highly prized. During this era, aged nihonshu ranging from three to ten years was reserved for celebrations, with the finest examples commanding premium prices among the samurai elite.

Everything changed with the Meiji Restoration. In the late 1800s, the government introduced the "zōkoku-zei" (brewing tax), fundamentally altering how nihonshu was taxed. Previously, taxes were collected when nihonshu was sold; under the new system, they were due immediately after brewing. No brewery wanted to wait years for revenue while risking spoilage or continued tax obligations.

This 'zokoku-zei' was abolished in 1944 and replaced with "kuradashi-zei"(tax upon shipment from brewery), but by then Japan had entered an era of mass production and consumption. The cultural appreciation for aged nihonshu had been lost to nearly a century of economic pragmatism. Only around 1970 did renewed interest in complexity and vintage appeal begin to emerge, as Japan's growing prosperity allowed for more diverse aesthetic values.

The Science of Serendipity: How Great Koshu is Born

At Hakushika, what outsiders call serendipity is actually the result of systematic observation. Every year, the brewery conducts "so-nomikiri"—early tasting inspections of their 400-500 storage tanks. This rigorous annual review examines every tank containing nihonshu at various stages of maturation.

"During one of these tastings, we found nihonshu that had developed beautifully over time," explains toji Tome-san. "Rather than being planned from the design stage, we were taught by the nihonshu itself. From there, we began to think about creating more koshu deliberately." Thanks to the comparison tasting of 400-500 tanks, the team captured the clues of the characteristics of nihonshu that can age beautifully, including polishing ratio, acidity level, amino acid level and so on.

What factors influence koshu's flavor development? When I asked this question, Tome-san outlined the key elements:

Temperature acts like a conductor for the aging orchestra. "The higher the temperature, the faster the aging progresses. But temperature fluctuations can cause problems, so maintaining stable, relatively low temperatures—15°C or below—is important for long-term storage," Tome-san explained.

The role of amino acids challenges common assumptions. While many believe higher amino acid content creates better aged sake, Tome-san disagrees: "Nihonshu with high amino acids tends to have rough flavors—what we'd call lower-grade nihonshu. When aged, the reactions are stronger, but the rough flavors come along with them." Quality over quantity, it seems.

Pasteurization presents an interesting paradox. "Pasteurization stops enzyme activity, actually slowing the aging process but providing stability," Tome-san notes. Sometimes slowing down creates better results—a lesson in brewing patience.

Added brewing alcohol is also interesting. "Aroma components dissolve into alcohol rather than water," Tome-san explains. "During aging, these components don't volatilize because we keep it sealed, so they continue to develop and change." The alcohol becomes a vessel for flavor evolution.

But perhaps most importantly, Tome-san returns to fundamentals: "the quality of the finished nihonshu. Well-balanced, clean-tasting nihonshu becomes an even better koshu when aged and mellowed." Great koshu, it turns out, begins with great sake.

Deconstructing the 10-Year Koshu: From Rice to Glass

Hakushika's 10-year koshu begins with 100% Yamada Nishiki rice from Hyogo Prefecture, polished to 70% (removing 30% of the outer grain). The choice of this "king of nihonshu rice" reflects their commitment to quality from the foundation up.

Tasting Notes: Complexity in Harmony

Appearance: Pale golden amber, translucent and luminous.

Nose: The aroma offers a deeply savory experience, beginning with a veil of umami-rich soy and unfolding into layers of marzipan, honey, toasted cashew, burnt sugar, candied fruit, brown sugar syrup, a touch of tonka bean, and more soy sauce. Additionally, it displays the hallmarks of the Maillard Reaction: nutty toast, caramel, and warm spice.

Palate: The texture is rich, creamy, and almost dessert-wine-like—medium-sweet, yet balanced by fresh acidity and elevated by dense umami. Complex yet approachable, with sweetness balanced by sufficient acidity, giving a long yet refreshing finish without heaviness.

Serving: "Room temperature to slightly warmed would be good," suggests Tome-san. When warmed, the sweetness becomes more pronounced and the nihonshu opens up beautifully, revealing layers of flavor that remain hidden when chilled. The brewery recommends pouring it over vanilla ice cream as a dessert—a playful application that demonstrates the nihonshu's versatility and natural affinity for sweet applications.

European Appreciation: Mingling Cultures

The response to Hakushika's koshu in Europe has been remarkably enthusiastic, particularly in countries with strong wine cultures. "I'm really surprised by the strength of reaction in places like Italy and Spain," notes Matsuki-san from the brewery's Overseas Business Division. "People seem to prefer more unique styles of nihonshu—they have a broader palate acceptance."

For instance, in Italy, innovative pairings with aged cheeses, especially Parmigiano-Reggiano, have created new appreciation for koshu. The country's Milano Sake Challenge even features a food pairing category for nihonshu that pairs with Parmigiano-Reggiano, where koshu and aged nihonshu frequently receive recognition. In Spain, consumers often demonstrate remarkable familiarity with the Japanese words for aged nihonshu, "koshu". "When they taste it, they immediately say it's very similar to Jerez (Sherry). They're amazed that this is Japanese nihonshu—they appreciate its depth."

This sophisticated response stems from established wine culture: "People who are used to drinking wine and thinking about daily food pairings can imagine what might work well—there's a cultural foundation for that kind of thinking," the sales representative explained.

Can You Make Koshu? Creating Aged Nihonshu at Home

For nihonshu enthusiasts inspired to experiment with aging, the answer is yes—with proper storage, koshu can be created at home. The key requirements are consistent temperature (15°C or below), darkness, and avoiding temperature fluctuations, just like wine. Temperature significantly affects aging speed: "For every 5°C difference in temperature, the reaction speed significantly changes—the lower the temperature, the slower the aging process," Tome-san explained.

This means patient collectors can experiment with different storage temperatures to influence their nihonshu's development rate. However, Tome-san emphasizes a crucial distinction: not every nihonshu ages gracefully. The quality and balance of the original nihonshu determines whether time will enhance or diminish its character.

For home aging, choose nihonshu with good acidity balance, avoid anything already showing signs of oxidation, and maintain consistent cool storage. Most importantly, taste periodically—aging nihonshu is a dialogue between time, temperature, and the original liquid's potential.

Standardization and Innovation

Currently, no official government standards exist for koshu classification. However, voluntary organizations are establishing guidelines. "The Long-term Aged Nihonshu Research Group defines aged nihonshu as 'nihonshu aged at the brewery for three years or more, excluding sugar-added nihonshu,'" explains Tome-san. "There's also the Toki Sake Association, which sets its own standards and offers 'Toki Sake' certification."

The challenge lies in koshu's inherent unpredictability. Each brewery develops different styles, and even within the same brewery, different vintages can vary significantly. Like wine, this variation becomes part of koshu's appeal—the exploration and discovery of how different conditions create unique expressions of time and terroir.

Conclusion

In Hakushika's philosophy, nihonshu brewing requires connecting every step carefully. "Each process in nihonshu making—if any one element is missing, you can't make good nihonshu. From raw material processing to the finished product, everything must be linked together," explains Tome-san.

This meticulous attention extends to their koshu program, where what began as accidental discovery has evolved into deliberate exploration of time's transformative power. Their 10-year koshu represents not just aged nihonshu, but nihonshu that proved worthy of aging.

Europe's enthusiastic reception suggests that koshu speaks a universal language of complexity and time that transcends cultural boundaries. Whether experienced with Parmigiano-Reggiano in Milan, compared to Sherry in Madrid, or paired with pecan nuts at a German trade fair, koshu demonstrates nihonshu's remarkable ability to find resonance with sophisticated palates worldwide.

The brewery's message to international audiences reflects this discovery: "Please try it once—you can't understand its quality without tasting it. That's where the first step begins."

As I discovered at ProWein, sometimes the most profound discoveries are indeed serendipitous. But as Hakushika demonstrates, recognizing and nurturing those serendipitous moments requires centuries of expertise, systematic attention, and the wisdom to let time reveal what intention alone cannot create.

Technical Specifications

Hakushika Koshu 10-Year

Brewery: Tatsuuma-Honke Brewing Co., Ltd. (辰馬本家酒造)

Founded: 1662 (363 years of operation)

Location: Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture (Nada district)

Rice: 100% Yamada Nishiki from Hyogo Prefecture

Polish Ratio: 70% remaining (30% polished away)

Aging: More than 10 years at constant 15°C

Style: Honjozo-based koshu with brewing alcohol

Japanese Sake Meter Value: -6 (sweet)

Acidity: 1.7-1.8

Yeast: Kyokai #701 (low-temperature brewing optimized)

Awards:

Grand Gold Medal : National Kan sake award 2024Gold Medal : Wine Glass Award 2025

Gold Medal : KURA MASYER 2025

Top of Best : Bishu competition 2024 (*Top of Best = Top of Gold Medal)

Best Served: Room temperature to lightly warmed (40-45℃)

Glossary

Koshu (古酒): Aged nihonshu, typically matured for three or more years

Toji (杜氏): Master brewer responsible for nihonshu production

Miyamizu (宮水): The famous brewing water of Nada. While most of Japan has soft water, miyamizu is distinguished by its rich mineral content—particularly potassium and phosphoric acid—that is exceptionally beneficial for sake brewing, earning it the revered name "miyamizu" (shrine water)

Kanzake (燗酒): Warmed or heated nihonshu

Honjozo: Premium nihonshu category with small amounts of added alcohol

Yamada Nishiki: Sake-specific rice. Often called the "king of nihonshu rice"

Special thanks to President Tatsuuma-san for making this article possible, and to Toji / Tome-san, Merchandise Dept. / Ohnishi-san, and Overseas Business Div. / Matsuki-san for their generous time and insights during the interviews.

Picture credit: Tatsuuma-Honke Brewing Co., Ltd. and Grape and Rice

偶然が生んだ発見:老舗酒蔵白鹿が切り拓く古酒の世界

日本最高峰の日本酒産地から、辰馬本家酒造の熟成古酒への意外な旅路

筆者はオランダでワインと日本酒の講師をしている。オランダでの日本酒の認知度は着実に上がっており、日本料理と合わせるだけでなく、西洋料理のワインペアリングコースの一部として日本酒を提供するレストランが出ており、注目度が高く、日本酒を知りたいという要望も高い。この記事は、日本酒とワインを両方楽しみたい愛好家に向けに執筆している。

はじめに:意外な発見

ProWeinのマスタークラスで、砂糖でコーティングされたピーカンナッツが驚くほどの速度で皿から消えていく。白鹿の10年古酒から生まれるメイラード反応の香りが、甘くカリカリのピーカンナッツと織りなす協調は危険なほど中毒性があり、永遠に食べ続けられそうだった。

その後、見本市を歩き回りながら白鹿のブースにたどり着いた時、まだあのペアリングのことを考えていた。社長の辰馬さんにどうやってこの古酒が生まれたのかと尋ねた時、彼の答えは驚くほど謙虚だった:「偶然の発見でした」。

その言葉が私の好奇心をかき立て、この特別な古酒の背後にいる人々へのインタビューに導いた。

363年の歴史と基盤

兵庫県は日本の国内日本酒生産量の約30%を担い、全国最大の日本酒産地として知られている。兵庫県内でも、大阪と神戸の間に位置する灘地区はその最高峰として名高く、白鹿をはじめ数々の名門蔵が軒を連ねている。

辰馬本家酒造は、1662年から灘地区の西宮で日本酒を醸し続ける老舗の酒蔵 である。日本の江戸時代に辰馬吉左衛門によって創業されたこの同族経営の酒蔵は、現在15代目だ—約4世紀にわたる驚くべき継続性である。

「白鹿」(はくしか)という名前は、宮中の庭で銅牌(どうはい)を着けた千歳の白鹿に出会った皇帝の中国の伝説から取られている。その鹿は長寿と幸運の象徴となった—蔵の永続的な遺産にふさわしい比喩である 。

灘の中心に位置する白鹿は、この地域を日本酒生産の代名詞にした六甲山からの有名な醸造水「宮水」の恩恵を受けている。蔵の哲学は「料理と調和する旨味豊かな日本酒」を醸すことだ。このアプローチは、古酒開発も同様だ。

失われた伝統:武士の贅沢品から税制による絶滅まで

白鹿の発見が偶然と感じられる理由を理解するには、なぜ古酒がこれほど稀になったかを最初に理解しなければならない。江戸時代(1603-1867)の終わりまで、熟成日本酒は高く評価されていた。この時代、3年から10年熟成の日本酒は祝い事のために取っておかれ、最高級品はプレミアム価格で取引された。

明治維新ですべてが変わった。1800年代後期、政府は「造石税」を導入し、日本酒の課税方法を根本的に変えた。以前は日本酒が売られた時に税が徴収されていたが、新制度では醸造直後に税を払わなければならなかった。腐敗のリスクや継続的な税務義務を抱えながら、何年も収益を待つ蔵はなかった。

造石税は1944年に廃止され、蔵出税に移行されたが、戦後の混乱を経て、日本は大量生産と大量消費の時代に入り、熟成日本酒への文化的評価は、約1世紀の経済実用主義により失われていた。1970年頃になってようやく、日本の成長する豊かさがより多様な美的価値を可能にし、複雑さとヴィンテージ魅力への関心が再び現れ始めたのだ。

偉大な古酒はいかに生まれたか

白鹿で偶然と呼ぶものは、実は体系的観察の結果である。毎年、蔵では400〜500本の貯蔵タンクの「総呑み切り」貯蔵段階の様々な日本酒を含むすべてのタンクを検査する厳格な年次レビュー—を実施している。

「これらのテイスティングの中で、時間を経て、美しく熟成した日本酒を見つけました」と杜氏の登米さんは説明する。「設計段階から計画されたのではなく、日本酒自体に教えられたのです。そこから、より多くの古酒を意図的に造ることを考え始めました。」400〜500本のタンクの比較テイスティングのおかげで、チームは精米歩合、酸度、アミノ酸度などを含む、美しく熟成できる日本酒の特徴の手がかりを捉えていたのだ。

古酒の味わい発達にはどんな要因が影響するのか?この質問に対して、登米さんは主要な要素を説明した:

温度は熟成オーケストラの指揮者のような働きをするようだ。「温度が高いほど、熟成は早く進みます。しかし温度変動は問題を起こす可能性があるため、安定した比較的低い温度—15℃以下—を維持することが長期保存には重要です」と登米さんは説明する。

アミノ酸の役割は予想に反するかもしれない。より高いアミノ酸含有量がより良い熟成酒を作るという考えには、登米さんは異なる意見を持つ:「高アミノ酸の日本酒は荒い味わいになる傾向があります—荒い味わいとはいわゆる下級の酒です。アミノ酸により熟成反応がより強くなりますが、荒い味わいもついてきます。」量より質ということのようだ。

火入れは興味深いパラドックスだ。「火入れは酵素の活性を止めるため、熟成プロセスは遅くなりますが、熟成が安定します」と登米さんは述べる。時には遅くすることがより良い結果を生む—醸造における忍耐だ。

醸造アルコールの添加も興味深い。「香り成分は、アルコールに溶けやすい性質があります 。熟成中、密閉したタンクに貯蔵しているためこれらの成分は揮発せず、変化を続けます。」と登米さんは説明する。アルコールは味わいの進化の器となる。

最も大切なのは、登米さんが繰り返し語る「基本に立ち返ること」ということだ。「つまり、出来上がった日本酒そのものの品質が重要だということ。バランスが良く、雑味がなく、後味がすっきりした日本酒こそが、熟成によってまろやかさを増し、より優れた古酒になります。美味しい古酒は、もともと美味しい酒から生まれるのです。」と、登米さんは言う。

10年古酒の解剖:米からグラスまで

白鹿の10年古酒は、兵庫県産山田錦を100%使用し、70%まで精米される(外側30%を削り取る)。この「酒造好適米の王」を使うことは、品質へのこだわりを反映している。

テイスティングノート:調和における複雑さ

外観: 淡い金色の琥珀、透明で光沢がある。

香り: 香りは深く旨味豊かな。醤油の複雑さに始まり、マジパン、蜂蜜、トーストしたカシューナッツ、焦がした砂糖、砂糖漬け果実、黒糖シロップ、トンカ豆のタッチ、さらなるまた醤油の層へと展開する。さらに、メイラード反応の特徴:ナッツのようなトースト、カラメル、温かいスパイスが顕著。

味覚: 食感は豊かで、クリーミー。デザートワインのような—中程度の甘さだが、新鮮な酸味とバランスを取り、密度の高い旨味により引き上げられる。複雑だが親しみやすく、甘さは十分な酸味でバランスが取れ、重さなしに長くも爽やかな後味を与える。

提供: 「常温から軽く燗をつけるのが良いでしょう」と登米さんは提案する。温めると、甘さがより顕著になり、日本酒が美しく開き、冷やした時には隠れている味わいの層を明らかにする。蔵では、バニラアイスクリームにかけるデザートとしての利用も提案している—日本酒の多様性と甘い用途への自然な親和性を示すユニークな応用である。

ヨーロッパでの評価:文化の融合

白鹿の古酒に対するヨーロッパでの反応は良く、特にワイン文化を持つ国々での興味が高いそうだ。「イタリアやスペインなどでの反応の強さに本当に驚いています」と蔵の営業担当大西さんは述べる。「人々はより独特なスタイルの日本酒を好む傾向があるようです。彼らはより幅広い味覚受容性を持っています。」

例えば、イタリアでは、熟成チーズ、特にパルミジャーノ・レッジャーノとの革新的なペアリングが古酒への新たな評価を作り出しています。同国の『Milano Sake Challenge』は、パルミジャーノ・レッジャーノに合う日本酒のフードペアリングカテゴリーさえ設けており、その中で熟成古酒がすでに認知を受けている。スペインでは、日本酒に興味がある方々は熟成古酒を表す日本語「Koshu」を理解している人が多いそうだ。「味わうと、すぐにヘレス(シェリー)に非常に似ていると言います。これが日本の日本酒であることに驚愕し、その奥深さを評価するそうです。」

この洗練された反応は確立されたワイン文化に起因している:「ワインを飲むことに慣れ、日々のフードペアリングを考えている人々は、何が良く合うかを想像し、そのような思考の文化的基盤があるようです」と海外事業部松木さんは説明した。

古酒は作れるのか?家庭での熟成日本酒作り

答えはイエスである—適切な保管があれば、古酒は家庭で作ることができる。大事なことは一貫した温度(15℃以下)、暗さ、温度変動の回避で、ワインと同様である。温度は熟成速度に大きく影響する:「温度が5℃違うごとに、反応速度は大きく変わります—温度が低いほど、熟成プロセスは遅くなります」と登米さんは説明した。

これは、つまり、忍耐強いコレクターは、日本酒の熟成速度に影響を与えるために、さまざまな保存温度を試すことができるということです。しかし、登米さんは重要なポイントを強調する:すべての日本酒が優雅に熟成するわけではない。元の日本酒の品質とバランスが、時間が特徴を向上させるか減少させるかを決定する、ということだ。

家庭熟成には、良い酸味バランスの日本酒を選び、既に酸化の兆候を示しているものは避け、一貫した冷涼保管を維持する。最も重要なことに、定期的に味見をすること—日本酒の熟成は時間、温度、そして元の液体の潜在能力との対話である。

標準化と革新

現在、古酒分類に関する公式政府基準は存在しない。しかし、いくつかの団体がガイドラインを確立している。「長期熟成酒研究会は熟成日本酒を『蔵で3年以上熟成させた日本酒で、糖類添加日本酒を除く』と定義しています」と登米さんは説明する。「また、独自の基準を設け『刻(とき)SAKE』認定を提供する『刻(とき)SAKE協会』もあります。」

古酒には固有の予測不可能性がある。各蔵が異なるスタイルを発達させ、同じ蔵内でも異なるヴィンテージは大きく異なる可能性がある。ワインのように、この変動が古酒の魅力の一部となる—異なる条件が時間とテロワールの独特な表現をどのように作り出すかの探求と発見である。

最後に

白鹿の哲学では、日本酒醸造はすべての工程に注意を払っている。「日本酒造りの各プロセス—一つの要素でも欠けていると、良い日本酒は造れません。原料処理から完成品まで、すべてがつながっていなければなりません」と登米さんは説明する。

この細心の注意は古酒造りでも同様で、偶然の発見として始まったものが時間の変革力の意図的探求に発展した。彼らの10年古酒は単なる熟成日本酒ではなく、熟成に値することが証明された日本酒を表している。

ヨーロッパでの反応は、古酒が文化的境界を超越する複雑さと時間の普遍的言語を話すことを示唆している。ミラノでパルミジャーノ・レッジャーノと体験されても、マドリードでシェリーと比較されても、ドイツの見本市でピーカンナッツと組み合わせても、古酒は日本酒の世界中の洗練された味覚との共鳴を見出す驚くべき能力を示している。

国際的な聴衆に対する蔵のメッセージはこの発見を反映している:「一度お試しください—味わうことなしにその品質は理解できません。そこから最初の一歩が始まります。」

ProWeinで発見したように、時に最も深遠な発見は確かに偶然である。しかし白鹿が示すように、そのような偶然の瞬間を認識し育てることは、何世紀もの専門知識、体系的注意、そして意図だけでは創造できないものを時間に明らかにさせる知恵を必要とする。

技術仕様

白鹿 古酒 10年

醸造所:辰馬本家酒造株式会社

創業:1662年(363年の歴史)

所在地:兵庫県西宮市(灘地区)

米:兵庫県産山田錦100%

精米歩合:70%

熟成:15℃定温で10年以上

スタイル:本醸造ベースの古酒(醸造アルコール添加)

日本酒度:-6(甘口)

酸度:1.7-1.8

酵母:協会701号(低温醸造最適化)

受賞歴:

・全国燗酒コンテスト 2024 特殊ぬる燗部門 最高金賞受賞・ワイングラスでおいしい日本酒アワード 2025プレミアム熟成酒部門 金賞受賞

・美酒コンクール 2024 エイジド部門 金賞受賞【TOP OF THE BEST】※エイジド部門金賞の中で最高得点

・KURA MASTER 2025 古酒部門 金賞受賞

おすすめ提供方法:常温から軽く燗(40‐45℃)

用語集

古酒(こしゅ):熟成日本酒、通常3年以上熟成

杜氏(とうじ):日本酒生産の責任を負う杜氏

宮水(みやみず):灘の有名な醸造水。日本の大部分が軟水であるのに対し、宮水は豊富なミネラル含有量—特にカリウムとリン酸—により区別され、酒造りに特に有益で、崇敬の名前「宮水」(神社の水)を獲得している

燗酒(かんざけ):温めた日本酒

本醸造:少量のアルコール添加を伴う高級日本酒カテゴリー

山田錦:酒造専用米。しばしば「日本酒米の王」と呼ばれる

本記事を可能にしてくださった辰馬社長、インタビュー中に貴重な時間と洞察を惜しみなく提供してくださった杜氏の登米さん、商品部の大西さん、海外事業部の松木さんに感謝を申し上げます。

写真提供:辰馬本家酒造株式会社

お読みいただき、ありがとうございます!いいね、コメント、重ね読み、購読でサポートしていただけると嬉しいです。