Sake Interview #3: Kirei Shuzo—The 92% Polishing Ratio Revolution: Bone Dry Sake

Master Brewer Masahiro Nishigaki on Why Less Polishing Means More Flavor

**🇯🇵 日本語版は記事の下部にあります / Japanese version available below**

Interview with Kirei Shuzo's toji Masahiro Nishigaki on crafting bone-dry sake from 92% polished rice. Discover why minimal polishing and maximum precision create sake perfect for wine enthusiasts.

📍Who This Is For

Curious about sake? Hear directly from the person who makes it. Whether you work in wine retail or hospitality—or simply enjoy discovering standout bottles at home—this post is for you.

I'm Kazumi, a DipWSET and educator based in Amsterdam. With a background in wine and sake, I translate sake through a wine-savvy lens.

Sometimes a single sip can shift your entire perspective. At TEWATASHI in Amsterdam, I encountered Kirei Junmai (pure rice) Muroka (unfiltered) Nama (unpasteurized) Genshu (undiluted) 92—and that number gave me pause. A 92% polishing ratio. In an industry where premium sake typically means rice milled down to 50% or less, here was something barely polished at all.

The sake showed subtle green tints in the glass. The aromatics were restrained, particularly for fruit—instead offering toasted nuts, warm spices, and earthiness. The palate told a different story from typical sake: bone dry, structured, with pronounced umami and remarkable length. Despite minimal polishing, there was no trace of roughness. This wasn't about fruity aromatics or delicate sweetness. This was pure flavor and texture.

In today's sake market, with its preference for elegant, subtly sweet styles, Kirei 92 stands apart. It speaks directly to wine lovers who value structure and savory complexity over aromatic charm. Intrigued by this unconventional approach, I arranged an interview with Masahiro Nishigaki, the toji behind this distinctive sake.

The Brewery and Its Philosophy

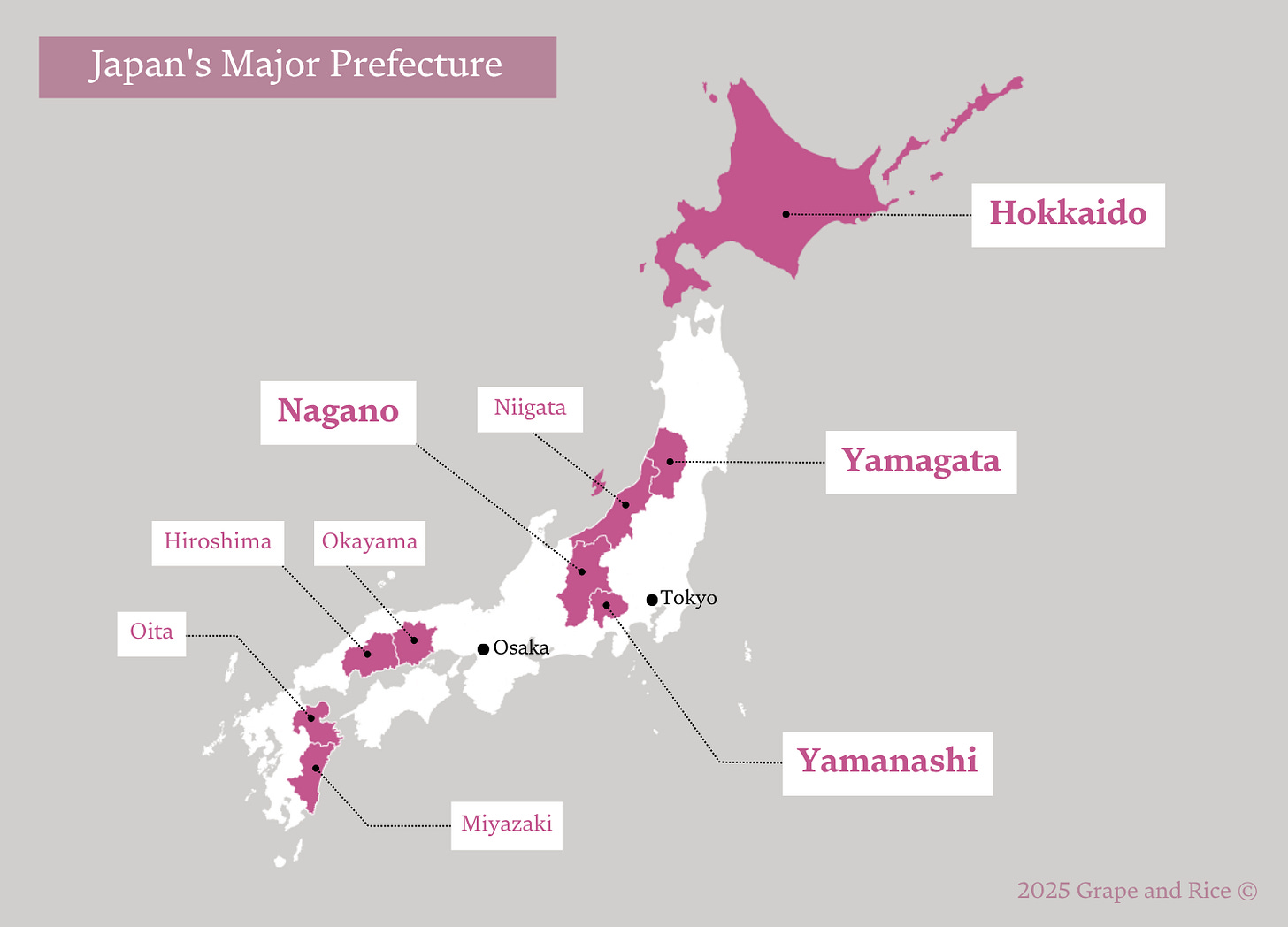

Kirei Shuzo has operated in Saijo, Higashihiroshima, Hiroshima prefecture since 1898. The name derives from the Japanese proverb "Cranes live a thousand years, turtles ten thousand"—a wish for longevity embedded in the brewery's identity.

Masahiro Nishigaki represents the second generation of his family to serve as Kirei's toji. With 35 years of brewing experience, including 28 as master brewer, he continues a tradition learned during a five-year apprenticeship under his father, Nobumichi. Interestingly, he has very low alcohol tolerance, but like many beverage professionals, he tastes and spits during evaluation.

Hiroshima prefecture occupies a special place in Japan's sake landscape. Home to the Annual Japan Sake Awards—the most prestigious competition in Japan—think of it as sake's Decanter World Wine Awards. The region is known for its exceptionally soft water. Even by Japanese standards, where water is already soft compared to Europe, Hiroshima's water is ultra-soft. This typically produces sake with gentle texture, rich aromatics, and subtle sweetness. Against this regional style, Kirei 92's bone-dry character becomes even more remarkable.

The Evolution of Low-Polish Sake

To understand the significance of 92%, consider sake's polishing categories: daiginjo requires milling to 50% or less, ginjo to 60% or less, and honjozo to 70% or less. Table rice typically sits around 90%. At 92%, we're entering largely unexplored territory. (Check out this post for more knowledge about polishing ratio.)

"It began 15 years ago with a suggestion from our sales team," Nishigaki recalls. "The idea was radical—what if we could create premium sake without the premium polishing? We started with just one tank—1,000 kilograms—as an experiment."

This represented a dual challenge: defying market conventions that equated high polishing with quality, and going against Hiroshima's tradition of gentle, subtly sweet sake. But Nishigaki had inherited his father's commitment to dry sake. They began conservatively with 80% polished rice, then gradually pushed boundaries to 92%.

Why is low-polish brewing so difficult?

The advantages of minimal polishing appear straightforward: speed. While milling to 70% requires approximately 10 hours and to 50% takes 50 hours, reaching 92% takes significantly less time. Higher yields and lower costs follow naturally. "At 90%, you're essentially just removing the outer husk," Nishigaki explains.

"When other breweries visit, they consistently express the same surprise," he notes. "How can sake of this quality be produced at such an accessible price point?"

However, the brewing challenges are substantial. The proteins and lipids retained in minimally polished rice create multiple complications. "If you brew conventionally, these components easily produce off-flavors and fermentation proceeds too rapidly due to too many nutrients for yeast," he explains.

The challenge intensifies with their choice to make muroka namagenshu—unfiltered, unpasteurized, and undiluted sake. This approach leaves no room for error, as every flaw becomes apparent.

Yet Kirei 92 shows remarkable refinement. The secret?

Applying Premium Techniques to The Challenges

"We brew our 80% and 92% polished sake using exactly the same methods as daiginjo," Nishigaki reveals.

This approach transforms the entire process. Without careful control, fermentation temperatures would naturally climb to 18-20°C and finish within 14 days, producing rough, unrefined flavors. Instead, Nishigaki's team maintains a steady 11°C through meticulous management, extending fermentation to 26-27 days. Every step requires precise timing, often measured in seconds.

The philosophy differs markedly from wine production. Where winemaking—even with meticulous care—emphasizes minimal intervention to express terroir, sake brewing embraces its need for constant, precise control.

Actually, the level of precision required is extraordinary: soaking times adjusted by seconds, temperatures controlled within a single degree Celsius. This isn't just attention to detail—it's a completely different type of craftsmanship.

"If you want to change the quality or style of sake, the quickest way is to change the toji," he says. Here, human technique is paramount.

So what exactly goes into this sake?

The rice is 100% Hattan Nishiki from Hiroshima prefecture, a variety known for producing clean, crisp sake. But rice characteristics vary annually based on weather conditions—grain size, starch structure, and moisture content all fluctuate. "Quickly assessing each year's rice condition is crucial," Nishigaki emphasizes. "We adjust soaking times by seconds based on these evaluations."

When I inquire about vintage variation—a concept central to wine appreciation—he maintains a different perspective. "Regardless of rice quality or weather conditions, maintaining our brewery's fundamental character is essential."

It's an approach reminiscent of Champagne's non-vintage philosophy: prioritizing consistency over vintage expression.

The yeast story reveals another layer of continuity. They've maintained the same strain for over 30 years, originally derived from Association No. 9 yeast and passed from father to son. "Yeast dramatically influences sake quality, particularly its aroma," he explains. "That's why we essentially never change it."

Even Hiroshima's celebrated soft water takes a backseat to technique. "Water influences the result, but the brewer's skill matters more," Nishigaki insists.

The Sake: Kirei Junmai Muroka Namagenshu 92

Rice: Hattan Nishiki (Hiroshima)

Polish: 92%

Yeast: Proprietary

SMV: +4 (positive numbers indicate dryness—the higher the number, the less residual sugar)

Acidity: 2.1

Alcohol: 16%

Tasting Note:

Clear with subtle green reflections in appearance.

The nose offers layers of toasted nuts, grains, earthiness, and spices, with background notes of hints of melon, lime zest, and fresh herbs. Complex aromatics reveal chestnuts, almonds, hazelnuts, cereals, and brown sugar.

On the palate, it's dry with higher acidity than typical sake. Full body, rich in umami and a precise long finish. At 16% ABV, it's lower than most genshu (undiluted sake)—achieved through careful water additions during fermentation rather than post-production dilution. Despite the minimal 92% polishing, there's no trace of roughness or astringency.

This is sake that prioritizes palate impact over aromatic appeal—a philosophy wine enthusiasts will recognize.

Service and Storage

"Sake reveals its true character around 20°C [68°F]," Nishigaki advises. "Consider cola—when cold, sweetness is muted. At room temperature, everything becomes apparent."

It's confident guidance from someone who knows his sake can withstand scrutiny. While delicious at various temperatures, that 20°C sweet spot deserves exploration—it's where nothing can hide.

As unpasteurized nama, refrigeration below 5°C is essential. The yeast remains active, making proper storage crucial.

Vision for the Future

When asked about his dream, Nishigaki identifies two primary goals.

First is succession. "Passing our techniques to the next generation is my most important responsibility." He's spent 20 years training his successor, recognizing that sake production requires teamwork. "Eight to nine people work together to create sake. The toji must be both technical expert and team leader. Without brewery harmony, you can make sake, but not good sake."

Second is a dream about ingredients. "I'd like to use only premium sake rice for all our production, including the 80% and 92% polished sake."

It reflects the eternal tension between artistic vision and economic reality.

Building Bridges

As someone who appreciates dry sake—and understands that many wine enthusiasts find typical sake too sweet with insufficient acidity—I see Kirei 92 as an important bridge between worlds. This is sake that speaks wine language: structure over sweetness, texture over aroma, complexity over simplicity.

My hope is for dining tables where wine and sake coexist as equals, each appreciated for their unique contributions to the meal.

In the Netherlands, Kirei 92 is available through importer Yoi Gokochi, its sister wine shop "Zuiver Wijnen", Japanese restaurants and so on. I'm grateful to Nishigaki-san for sharing his insights and to Dick from Yoi Gokochi for facilitating this conversation.

"I wanted to demonstrate that exceptional sake could be produced with 92% polished rice," Nishigaki told me.

The proof is in the glass. Kirei 92 doesn't simply challenge conventions—it establishes new possibilities, one precisely temperature-controlled fermentation at a time. For wine lovers seeking sake that speaks their language, this serves as an excellent translator.

Next time you're browsing sake selections, look for that 92% on the label. Your palate will thank you.

Picture credits: Kirei Shuzo and Dutch Wine Apprentice

精米歩合92%革命:大辛口の日本酒 - 亀齢酒造・西垣昌弘杜氏インタビュー

筆者はオランダでワインと日本酒の講師をしている。近年、オランダでの日本酒の認知度は着実に上がっており、日本料理と合わせるだけでなく、西洋料理のワインペアリングコースの一部として日本酒を提供するレストランが出ており、注目度が高く、日本酒を知りたいという要望も高い。この記事は、日本酒とワインを両方楽しみたい愛好家に向けに執筆している。

---

アムステルダムの日本料理店「TEWATASHI」で出会った一本の日本酒が、私の常識を覆した。「亀齢 純米無濾過生原酒92」。驚いたのは、その精米歩合だった。92%。つまり、ほとんど削っていない。

注がれた酒は、わずかに緑がかった色。香りは控えめで、ナッツやスパイス、栗のような香ばしさが感じられる。口に含むと、大辛口。しっかりとした旨味と骨格、そして長い余韻。にもかかわらず、雑味が一切なく、洗練された質感。香りに頼らず、味わいで勝負する。まさにワインラバーが評価するポイントそのものだった。

現在の日本酒市場では、軽やかで甘みを持つ酒、特に高精白でフルーティーな吟醸酒が主流となっている中で、このドライで味わい重視の日本酒は、良い意味で異色の存在だ。この酒の裏側を知りたくて、私は広島の亀齢酒造、西垣昌弘杜氏にオンラインインタビューを行った。

亀齢酒造と西垣杜氏

亀齢酒造は1898年に創業した広島県東広島市西条の酒蔵である。「鶴は千年、亀は万年」という日本の諺—長寿への願いが蔵の名前に込められている。

西垣昌弘杜氏は、親子2代で亀齢酒造の杜氏を務めている。酒造り歴35年、そのうち28年を杜氏として過ごし、父・信道氏の下での5年間の修業期間に受け継いだ伝統を守り続けている。興味深いことに、彼自身はアルコールに対する耐性が非常に低いが、多くの飲料のプロフェッショナルと同様、評価の際は口に含んで吐き出すという。

広島県は日本酒の世界で特別な位置を占めている。日本で最も権威ある全国新酒鑑評会の開催地—いわば日本酒版デカンター・ワールド・ワイン・アワードだ。この地域は格別に軟らかい水で知られている。日本の水はヨーロッパと比べてすでに軟水だが、広島の水はさらに軟水なのだ。これが典型的には、柔らかな質感、豊かな香り、ほのかな甘みを持つ酒を生み出す。この地域性を考えると、亀齢92の大辛口な性格はさらに注目に値する。

低精白酒の誕生背景

「92」とは精米歩合92%を指す。大吟醸酒が50%以下、吟醸酒が60%以下、本醸造酒でも70%以下、そして食用米が90%程度であることを考えると、92%という数字がいかに未開拓の領域かがわかる。

「15年前、営業チームからの提案で始まりました」と西垣杜氏は振り返る。「高精白なしでプレミアムな酒が造れるか?という過激なアイデアでした。最初は1タンク—1000キロ—だけ実験として造ってみました」。

これは二重の挑戦だった。高精白こそ高品質という市場の常識への挑戦と、広島の柔らかく、ほのかに甘い酒の伝統への挑戦。しかし西垣氏は父から辛口へのこだわりを受け継いでいた。最初は控えめに80%精米から始め、徐々に92%へと限界を押し広げていった。

低精白酒造りの困難さ

低精白の米を使うメリットは明確だ。まずスピード。70%まで削るのに約10時間、50%まで削るのに50時間かかるが、92%ならはるかに短時間で済む。また、削り捨てる部分が少ないため出来高も多く、製造コストが抑えられる。「90%なら玄米を一皮剥いただけで達成できる」と西垣杜氏は説明する。

亀齢酒造へは他の酒蔵からの見学も多いそうだが、「価格が安いのにこれだけ品質の高い酒ができることに、皆さん驚かれる」という。

しかし、酒造りの難易度は極めて高い。精米歩合92%や80%の米に残るタンパク質や脂質は、複雑な問題を引き起こす。「そのまま造ると、これらの成分が雑味を生み、酵母への栄養過多で発酵が急速に進みすぎてしまう」と西垣氏は説明する。

さらに、この亀齢92は無濾過生原酒—濾過も火入れも加水もしない酒造り—という選択により、挑戦はより困難になる。このアプローチでは、すべての欠点が露わになってしまうからだ。

にもかかわらず、亀齢92は驚くべき洗練さを見せる。その秘密とは?

大吟醸と同じ製法で造る低精白酒

「低精白の80%や92%の酒も、大吟醸とまったく同じ製法で造る」と西垣杜氏は語る。

この手法が、酒造りの全工程を一変させる。低精白米は管理しなければ、18度から20度まで品温が上がってしまい、14日程度で発酵が終わり、粗く洗練されていない味わいになってしまうそうだ。しかし西垣氏のチームは、細心の管理により11度を保ち、発酵期間を26日から27日まで延ばしている。すべての工程で秒単位の正確なタイミングが要求される。

ワイン造りの哲学とは明確に異なる。ワイン造りは細心の注意を払いながらも、テロワールを表現するための最小限の介入を強調する。一方、日本酒造りは常に正確なコントロールが必要だ。

実際、要求される精密さは驚異的だ。浸漬時間は秒単位で調整され、温度は1度単位でコントロールされる。これは単なる細部への注意ではない—まったく異なるタイプの職人技なのだ。

「酒の質やスタイルを変えたければ、杜氏を変えるのが一番早い」と西垣氏は言う。ここでは、人の技術が何よりも重要なのだ。

原材料へのこだわり

米は広島県産の「八反錦」を100%使用。クリーンでキレのある酒を生み出すことで知られる品種だ。しかし米の特性は天候により毎年変化する—粒の大きさ、デンプン構造、水分含有量すべてが変動する。「その年の米の状態を素早く見極めることが重要です」と西垣氏は強調する。「その評価に基づいて、浸漬時間を秒単位で調整します」と語る。

ヴィンテージによる変化—ワイン愛好家にとって中心的な概念—について尋ねると、彼は異なる見解を示した。「米の品質や天候がどうであれ、蔵の基本的な個性を維持することが不可欠です」。

シャンパーニュのノン・ヴィンテージ哲学を思わせるアプローチだ:ヴィンテージ表現よりも一貫性を優先する。

酵母の話はさらなる継続性の層を明らかにする。30年以上同じ株を維持し、元は協会9号酵母から派生したものを父から子へと受け継いでいる。「酵母は酒質、特に香りに劇的な影響を与えます」と西垣氏は説明する。「だから基本的に変えることはありません」。

広島の誉れ高い軟水でさえ、技術の前では脇役だ。「水は結果に影響しますが、造り手の技術の方がより重要です」と西垣氏は主張する。

日本酒の味わい

亀齢 純米無濾過生原酒92のスペックは以下の通り:

原料米:八反錦(広島県産)

精米歩合:92%

酵母:自家培養

日本酒度:+4(プラスの数値は辛口を示す—数値が高いほど残糖が少ない)

酸度:2.1

アルコール分:16%

テイスティングノート:

外観は澄んだ液体にわずかな緑の反射。

香りは、トーストしたナッツ、穀物、土っぽさ、スパイスの層が重なり、背景にメロン、ライムの皮、フレッシュハーブのヒントが感じられる。複雑なアロマは栗、アーモンド、ヘーゼルナッツ、シリアル、ブラウンシュガーを思わせる。

口に含むと、一般的な日本酒より高い酸度を伴うドライな味わい。フルボディで旨味が豊富、正確で長い余韻。16%のアルコール度数は原酒(無希釈の酒)としては低め—これは製造後の加水ではなく、発酵中の慎重な加水により実現している。92%という最小限の精米にもかかわらず、粗さや渋みは一切ない。

これは香りの魅力よりも味わいのインパクトを優先した酒—ワイン愛好家なら理解できる哲学ではないだろうか。

提供温度と管理

「日本酒が真の姿を現すのは20度(68°F)くらいです」と西垣杜氏は述べる。「コーラを考えてみてください—冷やすと甘さが抑えられますが、常温ではすべてが明らかになります」。

これは自分の酒を知っている人の自信に満ちた姿勢だ。広い温度で美味しいが、その20度という最適温度は探求する価値がある—何も隠せない温度だからだ。

火入れをしていない生(なま)として、5度以下での冷蔵保管が不可欠だ。酵母はまだ活きており、適切な保管が重要となる。

将来へのビジョン

彼の夢について尋ねると、西垣氏は2つの目標を挙げた。

第一は後継者育成だ。「技術を次世代に伝えることが、私の最も重要な責任です」。彼は20年かけて後継者の東健太郎氏を育成しており、酒造りにはチームワークが必要だと認識している。「8〜9人が協力して酒を造ります。杜氏は技術的な専門家であると同時に、チームリーダーでなければなりません。蔵の調和なしには、酒は造れても、良い酒は造れません」。

第二は原材料についての夢だ。「いつかすべて酒造好適米で造ってみたい」という原材料へのこだわりを述べる。「高精白だけでなく、80%や92%の低精白でも全て酒造好適米を使ってみたい」という。

コストや流行を鑑みて最高の仕事をすることは杜氏としての最も大事な側面だと思うが、こだわりを実現させたいという職人魂を見た気がする。

また、西垣氏は、ここ4-5年の日本酒の味わいの傾向について、「最近の日本酒は甘くなってきている」と指摘し、日本の消費者が求めているとはいえ、「個人的には違和感を感じる」と本音を語った。

私も個人的に辛口の日本酒が好みな上、ワインと比較すると、酸が低く少々甘すぎると捉えるワインラバーが多い中、この日本酒はワインラバーにぜひ手に取ってほしいと思う一本だ。ワインも日本酒も同じように楽しむテーブル、それが私の夢だ。

最後に

オランダでは、インポーター「酔い心地」で取り扱っており、系列のワインショップ「Zuiver Wijnen」オランダ国内のレストランやショップで入手可能だ。貴重な話をしてくれた西垣杜氏、この機会を作ってくれた酔い心地のディックさんに感謝する。

「92%の精米歩合でも、これだけの酒が造れることを証明したかった」という西垣杜氏の言葉が、今も耳に残っている。常識を覆す挑戦と、それを支える確かな技術。亀齢92は、日本酒の新たな可能性を示す一本だ。

次回日本酒を選ぶ際は、ラベルの「92%」という数字を探してみてほしい。きっとあなたの味覚が喜ぶはずだ。

お読みいただき、ありがとうございます!いいね、コメント、重ね読み、購読でサポートしていただけると嬉しいです。